Language is one of the most powerful political weapons. The ability to choose how state violence, such as drone warfare, is described is the ability to attempt to determine how it is understood. Consider the difference between the word ‘murder’, for example, and the word ‘neutralisation’. Though they can both be used to mean the same thing – the deliberate killing of a person – the word ‘murder’ is vividly emotive, whereas ‘neutralisation’ is vague, bureaucratic, and sterile. To say that a drone has been used to murder a person sounds much more negative – violent, gruesome, even – than to say that it has been used to neutralise a threat. For ‘neutralisation’ we could substitute, perhaps, equally banal words such as ‘interdiction’ or ‘prosecution’, lofty-sounding technical words with an aura of expertise and formality but which are also difficult to pin down to a precise meaning.

Language is one of the most powerful political weapons. The ability to choose how state violence, such as drone warfare, is described is the ability to attempt to determine how it is understood. Consider the difference between the word ‘murder’, for example, and the word ‘neutralisation’. Though they can both be used to mean the same thing – the deliberate killing of a person – the word ‘murder’ is vividly emotive, whereas ‘neutralisation’ is vague, bureaucratic, and sterile. To say that a drone has been used to murder a person sounds much more negative – violent, gruesome, even – than to say that it has been used to neutralise a threat. For ‘neutralisation’ we could substitute, perhaps, equally banal words such as ‘interdiction’ or ‘prosecution’, lofty-sounding technical words with an aura of expertise and formality but which are also difficult to pin down to a precise meaning.

Language, that is to say, often masks the horrors of drone warfare in ways that subtly work to sanitise and legitimise it. One of the key claims about drone warfare, after all, is that it is uniquely positioned to minimize harm, with the metaphors of ‘surgical precision’ and ‘pinpoint accuracy’ being used to suggest that drone strikes are a particularly clean, and therefore proportionate and defensible, form of aerial bombardment. But it is not only such clear uses of metaphor that function to obscure the nature of drone killing. Very often we see the use of what has become known as the ‘exonerative voice’ or the ‘past exonerative tense’, which is a specific way of constructing utterances in order to simultaneously declare that violence has been done and to obscure responsibility for that violence. When exonerative language is used to describe state violence, we are made aware of this violence in a specific way: a way that makes it seem perhaps accidental, or inevitable, or a benign or unimportant by-product of an automatic and legitimate process. Violence appears as anything but violent.

The Politics of Grammar

Perhaps the most direct way to explain the exonerative voice is through examples. Discussing the ubiquitous phrase “mistakes were made,” John Broder writes that this particular piece of innocuous-sounding jargon “sounds like a confession of error or even contrition, but in fact, it is not quite either one. The speaker is not accepting personal responsibility or pointing the finger at anyone else.” It is a linguistic sleight of hand through which people can simultaneously admit that something disagreeable happened and hide the fact that this disagreeable thing was an act (often a deliberate act) of wrongdoing for which people or groups can and should be held accountable.

Many writers have pointed out that this specific linguistic trick is often used to describe police killings. In a satirical piece structured as a style guide for using the past exonerative, Devorah Blachor shows how multiple accounts of the police killing of George Floyd in 2020 (the killing that sparked global waves of Black Lives Matter protests) failed explicitly to acknowledge that Floyd was murdered by police. Instead, they coyly referred to police misconduct, a death in custody, or to an incident in which an officer was disciplined for kneeling. The New York Times, for instance, wrote: “4 Minneapolis Officers Fired After Black Man Dies in Custody.” The past exonerative tense, Blachor archly writes, “transforms acts of police brutality against Black people into neutral events in which Black people have been accidentally harmed or killed as part of a vague incident where police were present-ish”.

Writing about the curious phrase “officer-involved shooting,” a deliberately ambiguous formulation which is often used to refer to police brutality, scholar Michael Conklin likewise argues that the awkward and indirect nature of the phrase fails to identify anybody as having actually done anything.

The phrase “officer-involved shooting” is not just grammatically ambiguous; it also deceptively implies that the officer did not do the shooting. This is because referring to someone as being “involved” in an act insinuates that he was only involved in some tangential way.

To the degree that state violence is intelligible at all when spoken about in this opaque register, it appears accidental or incidental, rather than as the central content of the reported event. This is no accident: the exonerative voice is a fantastically effective tool for the misrepresentation of violence.

Drone discourse, too, has its equivalent version of this rhetorical trick. Rather than saying that mistakes were made or that individuals died, however, responsibility for harm is displaced away from the drone or the drone crews and onto the strike itself. Read more

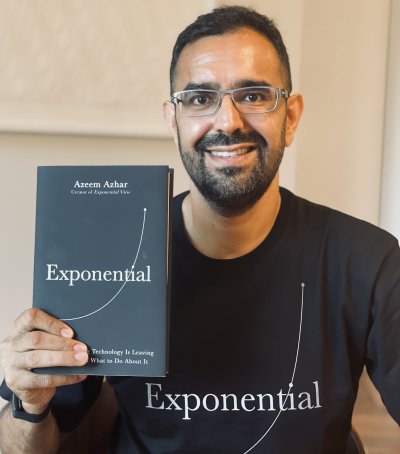

New technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) raise formidable political and ethical challenges, and these two books each provide a different kind of practical toolkit for examining and analysing these challenges. Through investigating a range of viewpoints and examples they thoroughly disprove the claim that ‘technology is neutral’, often used as a cop-out by those who refuse to take responsibility for the technologies they have developed or promoted.

New technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) raise formidable political and ethical challenges, and these two books each provide a different kind of practical toolkit for examining and analysing these challenges. Through investigating a range of viewpoints and examples they thoroughly disprove the claim that ‘technology is neutral’, often used as a cop-out by those who refuse to take responsibility for the technologies they have developed or promoted. Book Review: ‘War in Space – Strategy, Spacepower, Geopolitics’ by Bleddyn E. Bowen. Published by Edinburgh University Press, 2020

Book Review: ‘War in Space – Strategy, Spacepower, Geopolitics’ by Bleddyn E. Bowen. Published by Edinburgh University Press, 2020